Forget saintly mothers, what I needed were monsters like me

02/22/2023By Rachel Yoder

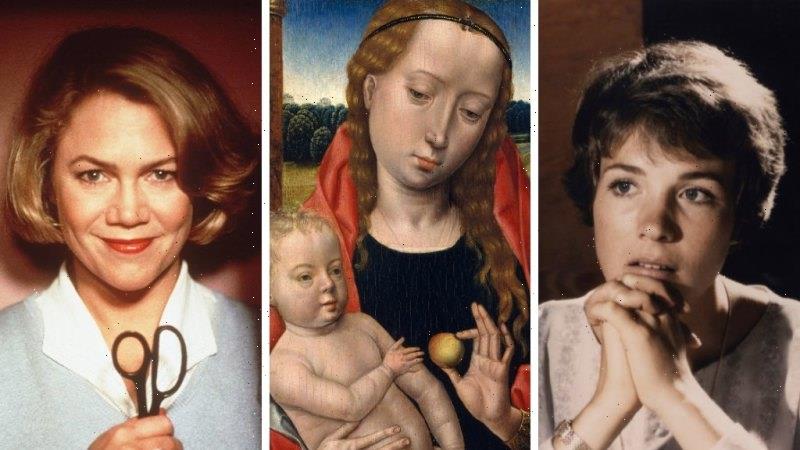

From left: Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music; Virgin and Child, artist unknown, early 16th century; Kathleen Turner in Serial Mom. Credit:

From a young age, the idea of mother loomed large, softly edged, silent. I grew up in a devout Mennonite family within a traditional community, where the men drank coffee and told stories while the women arranged casserole dishes on long tables and tickled toddlers weaving between their legs. This was the way things were: fathers talked, had ideas, dictated the direction of the family and church. Mothers made babies, food, clothing, but not decisions. They served their husbands and their children, wore dresses and coverings to show subservience to God. Who was a mother really, though? Who did she become when she wasn’t around her kids or her husband? Did she even exist without them? I didn’t think to ask these questions until I became a mother myself.

With my own babe in arms, I searched for another image of a mother, different than what I had seen in my own childhood, that aligned with how I felt in this new, perplexing state in which I found myself, sleep-deprived and sodden with milk, lovesick for an infant and intellectually depleted. I wasn’t myself any more, the self I had come to know, and motherhood called on me to become something more, someone else. But I couldn’t yet imagine who she was.

Rachel Yoder: “Motherhood called on me to become something more, someone else.″Credit:Nathan Biehl

Certainly there was the earliest mother I could remember, Mary herself, an unattainable ideal of purity and grace. Mary, who didn’t even need to sully herself with the act of sex in order to procreate and who sat serene, softly edged, silent in the hundreds of Renaissance paintings I’d passed by in my college semester spent in Italy. I didn’t know anything about her other than she had been a vessel for the Messiah, her value inextricably bound to the child she made, the love she had for him, and nothing else. I couldn’t be a Mary, forever posed with a precocious, glowing child on my lap, though I did try for a time. Maybe I’m not a writer any more, just a mother, I posited. Maybe if I sit here long enough in my robe with this child, I will learn what it means to be content, to desire nothing beyond this, for aren’t mothers a breed free from selfish wants?

Look at Maria in The Sound of Music, the 1965 film adaptation of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical. I certainly looked at her over and over again in one of the few movies I was allowed to watch as a child, Maria with her sexless haircut and straight-from-the-abbey style. She was, like Mary, a mother who manifested a family without the sordid detail of copulation to complicate the story. Look: suddenly she had seven children, and these children were given to her as a corrective, a lesson: to make her behave as a sensible, selfless young woman should. How do you solve a problem like Maria? You force her to be a mother.

Problem solved: Maria (Julie Andrews) and her brood in The Sound of Music.

Maria handles the rebellious children in a way none of the many previous governesses could, and the movie seems to suggest this is why Captain von Trapp ultimately falls in love with her, cutting free his former fiance, the sultry, rich, and kid-averse baroness. While Maria seemed to be having fun sewing play clothes from curtains and teaching the children their do-re-mis, something still didn’t sit right with the message that for this young woman, meaning and direction was found within the role of mother, that this was somehow the thing that was needed to tame and correct her youthful verve.

In my own early motherhood, as I searched for a mother who seemed like me or someone who I could feasibly be, I read books of which I now have little memory, just a haunting sense of how they vibrated through my body when I read. Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels made my stomach ache, still do when I reach to remember them, Lenú and her big, messy, passionate life. Every gear inside Lenú grinds against the next in an effort, a Herculean effort, simply to exist as she needs to exist, as a woman, an intellect, a mother, a person of varying passions and fierce dreams which she will not compromise.

Reading Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work: On Becoming a Mother was like staring at the sun, absolutely excruciating with its blinding brilliance. I highlighted: “My daughter quickly comes to replace me as the primary object of my care” and “My life has the seething atmosphere of an untended garden” and “…motherhood is a career in conformity from which no amount of subterfuge can liberate the soul without violence…” and “The state of motherhood speaks to my native fear of achievement. It is a demotion, a displacement, an opportunity to give up.” I related so acutely with Cusk’s writing that I almost had to abandon the book altogether. Too much like gazing in a mirror after a sudden disfigurement, knowing it’s you there but baffled and horrified by what you see.

The mother as unhinged, as impolite, as dangerous: I had never considered such a mother and I wondered, why not?

While reading Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, I finally opened my laptop after nearly two years of maternal disuse and typed there, in a new document, a passage that stirred a former self I had forgotten: “My plan was to never get married. I was going to be an art monster instead. Women almost never become art monsters because art monsters only concern themselves with art, never mundane things.” I thought I’d write an essay about this “art monster,” but I didn’t yet know what I would possibly say. I only knew that I was compelled by the idea of a woman and, moreover, a mother, being a monster. How terrifying. How dangerous. How powerful.

Of course I’d also read Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s foundational feminist text The Yellow Wallpaper in college and immediately liked it for its gothic creepiness. Certainly, I understood it was a story meant to critique the patriarchal control men exerted over women. And even at 20, I knew it was a commentary on motherhood, though at the time I couldn’t be certain what exactly it was saying.

Gena Rowlands in A Woman Under the Influence.Credit:Getty Images

At 36, now a stay-at-home mum who had stepped out of the workforce and stopped writing, The Yellow Wallpaper throbbed with significance. While no one had locked me in a room and there was not even a scrap of wallpaper in my home to peel from the walls, I saw Gilman’s story as a feminist fable about the ways in which women are trapped inside institutionalised structures of power and control that seem impossible to escape. A reasonable option, then, might be to lose one’s mind. I mulled this option as I sat in my own yellow living room with a small child, sometimes not seeing another adult for days, making up my own wild stories.

The mother as unhinged, as impolite, as dangerous: I had never considered such a mother and I wondered, why not? Why have I never seen messy mothers, angry mothers, unbrushed and unbathed mothers? Mothers who didn’t want to play, who didn’t want to cook, who didn’t want to sing another song or read another book? I was interested in these mothers because they seemed like real people rather than priceless paintings hung behind glass. Imagine: a mother who hasn’t been desexed and painted pastel, who doesn’t find her ultimate life’s purpose in her children. Who was she? And where?

I was terrified by the unhinged image I saw of mother in John Cassavetes’ A Woman Under the Influence (1974), but I couldn’t look away. The film presented a worst-case scenario as Mabel, the mother, falls apart in real time, losing her ability to just keep it together, as I had so often implored myself. Her husband commands “Just be yourself!” but it’s clear she can’t find a self to be. Eventually she’s institutionalised and given electroshock therapy, only to return home to the same scene she left. What’s changed? What’s progressed? A resounding silence answers.

Unhinged: Kathleen Turner in Serial Mom.Credit:Getty Images

On the other end of the filmic spectrum, John Waters’ Serial Mom delighted me with a jubilantly deranged serial-killer mom, played by Kathleen Turner, who torments suburbia, murdering one unsuspecting victim with a frozen leg of lamb. Here was a vision of domesticity turned on its head and then twisted again for good measure: a math teacher criticises her son, so Mother runs the guy over with her car. Her daughter’s date stands her up, so Mother stabs him with a fire iron. She’s a good mum, so good that she kills anyone who presents even the slightest threat to her children’s wellbeing. She’s “The Perfect Mother” taken to the most ludicrous, violent, and — some might argue — rational conclusions.

What most fascinated me in these portrayals of mother was their unruliness and anger. Behind the serene facade of maternal satisfaction was an entire complicated person. And it was this complicated person that I wanted to embrace in my own motherhood, a woman who loved her child dearly and who also fiercely loved her own mind. With children, compromise is inevitable, but I wasn’t interested in old agreements made before my time and without my consent. I wanted a new contract, still do, one that isn’t premised on a mother being happy with what she gets, but rather, with her deserving to have exactly what she wants.

Imagine Mary, a heretofore unsketched image of her that reveals to us an individual rather than an icon. What does she look like in this painting? Can you see the wrinkles, the sag of skin, the softness of her teasing smile? Look more closely, really look. Can you see her, not Mary now, but your own mum? Have you ever really seen her? And what, oh what, will be revealed when you finally look?

Rachel Yoder is the author of Nightbitch. She appears at the Wheeler Centre on March 3 and 4, as part of M/OTHER, a weekend of discussions running March 3-5. wheelercentre.com

Popular culture’s most unconventional mums

Lindy Percival celebrates six outlandish TV characters who subvert the maternal stereotype …

Morticia Addams, The Addams Family

Bypass Catherine Zeta-Jones’ weirdly bland matriarch in last year’s Netflix reboot and return instead to the original Morticia Addams for some genuine maternal quirk. Carolyn Jones was the pale-skinned, raven-haired oddball who turned countless young viewers onto goth chic in the 1960s TV series The Addams Family. When she wasn’t snipping buds off roses, knitting three-armed jumpers, or whispering sweet French nothings to husband Gomez, she was warning her kids about the dangers of playing outside in “all that blue sky and sunshine”.

Moira Rose, Schitt’s Creek

Credit:

It was clear from the moment revenue officials arrived at the Rose family mansion that financial ruin wasn’t about to dampen the deep-seated matriarchal narcissism at the heart of this dysfunctional lot. More focused on the fate of her beloved wigs than the welfare of her infantile adult “bebes”, Moira confronts her Schitty new reality with mounting hysteria and staggering self-absorption. After forgetting daughter Alexis’ middle name, she quickly flips the familial guilt trip: “We have so many disasters bombarding us right now, my dear, the middle name of an ungrateful child is hardly a priority.”

Betty Draper, Mad Men

Credit:AMC

She looks for all the world like your typical vanilla sitcom mum, but when icy Hitchcockian blonde Betty Draper aims a shotgun at her neighbour’s homing pigeons, it’s clear this woman has layers. Clinging to an ideal of domestic perfection that is already outdated when the series begins in 1960, Betty’s maternal charade slowly crumbles in the face of her husband’s infidelities. She can flip all the pancakes in the world, but when son Bobby swaps her sandwich for a bag of lollies during a school excursion, her simmering resentment makes it clear this is one mum who is not cut out for martyrdom. “Do you think I’m a good mother?” she wonders, later that night. Not so much, Betty, but selflessness was never your style.

Meg, Motherland

Credit:ABC

Imperfect motherhood assumes many guises in this BBC sitcom set against the parental minefield of the school drop-off. Frazzled Julia is already drowning under the weight of failed career, slack husband and judgy other mothers when alpha mum Meg moves in across the road, seemingly blitzing life with five kids and a rudely successful career. So it’s vaguely reassuring when the woman who “makes us feel like shit” reveals the chaos underpinning it all during a wild, boozy night out. “I love my kids, I love my job, I love my life,” she tells Julia, “but in order to survive I’ve got to blow it up every now and again.”

Edina Monsoon, Absolutely Fabulous

Credit:

The Bolly-swigging fashion victim at the head of Monsoon PR flips the mother-child paradigm, playing tantrum-throwing toddler to her sensible, straight-faced daughter. Daggily dressed and impervious to the nonsense, Saffron doles out disapproval with the scolding tone of an older, wiser and thoroughly fed-up family member: “You live from self-induced crisis to self-induced crisis,” she tells her mess of a mother. “Somebody chooses what you wear … someone tells you what to eat, and, three times a week, someone sticks a hose up your bum and flushes it all out of you.”

Wendy Byrde, Ozark

Credit:Netflix

As a modern-day Lady Macbeth to her money-laundering husband Marty, Wendy Byrde might be the most villainous of Ozark’s many miscreants. Pitting her wits against the FBI, a Mexican drug cartel, and her increasingly censorious teenagers, she might tell anyone who’ll listen that she’s only doing what any protective mother would. But at several key turning points, her inner psychopath reveals itself and by the time she begs her abusive father not to take her children away – “I will be so good” – she’s forfeited any skerrick of sympathy we might have felt: the mother of all villains just got what was coming.

A cultural guide to going out and loving your city. Sign up to our Culture Fix newsletter here.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article