Awakening from My American Dream

11/15/2021“What’s it like to live the American Dream?”

I get this reductive question a lot.

If you are curious about my unvarnished reality, here is a corner from which to begin: On weeknights, my husband and I often order Chinese delivery. When the food arrives, my husband always answers the door, while I stay out of sight. I’m certain that he attributes this to my laziness; I’ve never bothered to correct him. But, here, I confess the truth: I cannot bear the guilt.

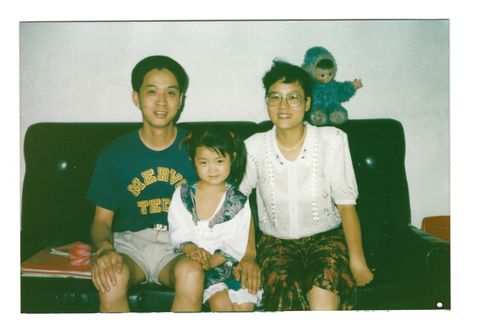

In 1994, at age seven, I moved with my parents from north China to New York City. Overnight, we went from documented citizens to undocumented immigrants, and my parents went from professors to menial laborers. After work, we picked through trash for treasures and recyclable cans. Long after the illegality of our status passed, the hunger, fear, and shame of those years weighed on me. I feel them most before echoes of my childhood: the soot on the hands of an elderly couple going through garbage; the purple of a deliveryman’s face as he pedals against wintry gusts.

My father is the biggest patriot I know. He met America through Hemingway and Twain, and despite everything, he still sees it as the land of opportunity. I aspired to make my father proud, prove him right. So when I disembarked at JFK, I set about summiting the American Dream. At the peak, we would find full acceptance, just like any white, natural-born American.

My father is the biggest patriot I know. He met America through Hemingway and Twain, and despite everything, he still sees it as the land of opportunity.

Back then, we made our home in one room, padded by some old comforts: dumplings on Sundays, handmade from kitchen scrap; songs from Chinese cassettes; a curtain we had packed. But more than that, I made my home in our Dream—whenever I felt hopeless, I remembered that I just needed to locate the peak, where I would finally find that unconditional belonging.

Yet each time I thought I had summited, I found only more rocky terrain. At Swarthmore College’s freshman orientation, my adviser laughed in my face when I expressed hope of attending a top law school. His laughter stalked me around campus, and I figured that when I proved him wrong, I would find the peak. But even at Yale Law School, the laughter continued. It came from a classmate as he bragged about paying an undocumented family (he assumed, given their race) to clean his apartment. It came from professors who conflated me with other Asian students—men and women—and joked that none of us seemed to know our names. It emerged from my first-year roommate, who found out about my undocumented past and broadcast it like just another mundane piece of gossip.

More than two decades after I first landed at JFK, I earned my citizenship. Yet, border control detained me whenever I reentered. In little rooms with handcuffs on display, officers interrogated me and searched my body. Once, I flew to New York with a British friend. She got in just as easily as the white Americans; my clearance took an hour.

I kept climbing. After years of discrimination and harassment, I finally made partner at the national law firm I had joined—the only person of color to do so that year. The head of the firm misspelled my name—and my name only—on the announcement, never bothering to apologize.

Still gripping the Dream, I started my own firm. I began building toward the values that pulled me into the law: the careers of Thurgood Marshall and Ruth Bader Ginsburg; representing the children and the marginalized of American society. It is here that I awakened. Because I know now that children today still face the very same barriers I confronted decades ago.

I see that the Dream is just a white plane on which I can never make an unconditional home.

My work has alerted me to the ways my former life lives on without me. And I see that the Dream is just a white plane on which I can never make an unconditional home, where I am told daily I am unwelcome, no matter how many dumplings I order or how regularly I hide from their delivery person. I’ve had both the privilege and curse of living at every socioeconomic level. I make my home now in purgatory, belonging to neither this world nor that.

We champion cherry-picked stories—the homeless kid who graduated from Harvard; the undocumented girl who became a courtroom lawyer—because equal opportunity is so sparse that we must collect every crumb of evidence. For every superficial example, there are millions still living out the sentence they received at birth. Our American Dream values material wealth over mental health, belongings over belonging. It discards the indispensable elements of the human condition. In the name of a dream—by definition, an illusion—America demands its marginalized to throw themselves against systemic barriers just to climb material ranks bloodied and alone.

I do not have the heart to tell my father that I no longer believe in our Dream. But the truth is that I now hope the Dream as a trope will one day cease to exist—because there will be less for the marginalized to overcome, because belonging and acceptance will be evenly assigned at birth. What kind of country might we build if we dared to mark that as our summit instead?

Qian Julie Wang is the author of Beautiful Country: A Memoir (Doubleday Books).

Source: Read Full Article