Alan Heller, Who Made Plastic Housewares Beautiful, Dies at 81

08/23/2021Alan Heller, the manufacturer of elegant, often whimsical but always affordable housewares and furniture that married high design with prosaic plastic, died on Aug. 13 at his home in Manhattan. He was 81.

Barbara Bluestone, his companion, who confirmed the death, did not specify a cause but said he had been in poor health for many years.

The son of a housewares manufacturer, Mr. Heller was a year out of college in 1966, pivoting from an extremely brief career selling ironing board covers, when he saw a set of stackable plastic dishes and cups in a museum exhibit.

The dinnerware was the work of Massimo Vignelli, the Italian designer and graphic purist responsible for the New York City subway map, the Bloomingdale’s logo and other visual staples of the late 1960s and 70s.

The pieces were astonishingly simple, like the Helvetica font that Mr. Vignelli would become famous for. The plates had rims designed for stacking, and the coffee cups, which were big enough to accommodate just a shot or two of espresso, had handles that sprouted from the cup rims like arching water slides. The dinnerware had won the Compasso d’Oro, Italy’s design Oscar, in 1964, and a set had been acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York for its permanent collection.

Mr. Heller was smitten. He sought out Mr. Vignelli, who by then had moved to New York City, and the two made a deal to produce the pieces again. (The original manufacturer, a Milanese company that had also made Mickey Mouse ashtrays, had gone out of business.) But first some changes had to be made.

Americans liked their caffeine in big mugs (few were drinking shots of espresso then), and they tended to fill those cups to the brim, which meant that Mr. Vignelli’s refined handle design and notched cup rim had to be modified, to stop hot coffee from spilling onto the American drinker’s hand.

“It was like pulling the wings off a butterfly,” Mr. Vignelli often said of those changes, as recalled by Michael Bierut, former vice president of graphic design at Vignelli Associates. “All you’re left with is a bug.”

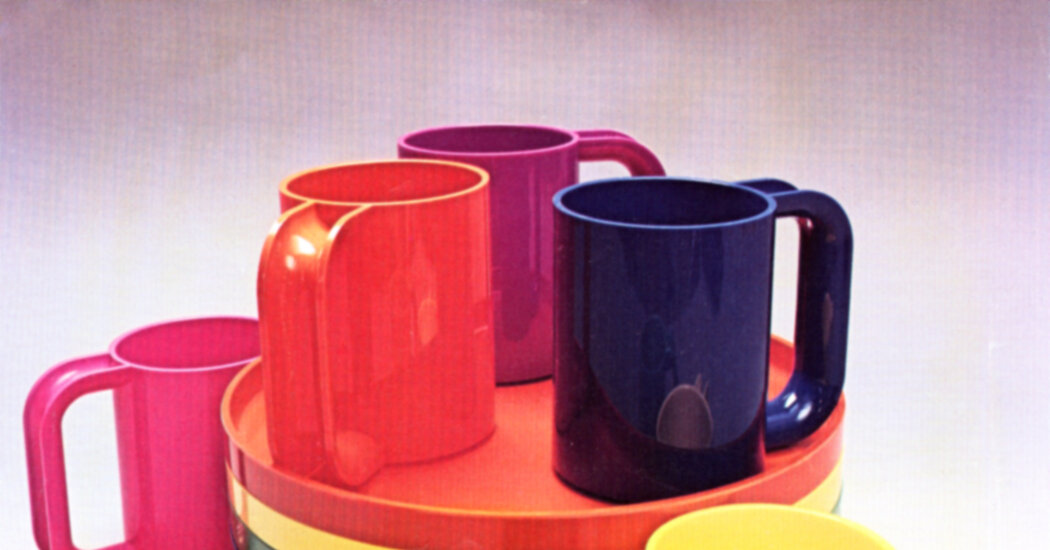

But Mr. Vignelli was not really bitter, and he, his wife and design partner, Lella Vignelli, and Mr. Heller became lifelong friends and collaborators, making Heller dinnerware, as they called it, in many iterations, most spectacularly in rainbow colors. To Americans of a certain age, Heller dinnerware is as potent a madeleine to the 1970s as a Marimekko print.

“Alan understood how good design could make your life more fun and more pleasurable,” said Suzanne Slesin, a longtime design writer and publisher and a former reporter for The New York Times. “He made plastic objects that had integrity and beauty — something you wanted to collect and show off — and were affordable. It was design for everyone.”

When, in the early ’90s, the puckish French designer Philippe Starck wanted to make a toilet brush, he turned to Mr. Heller to develop the technology for it and to make its special molds. The brush, marketed as Excalibur, for King Arthur’s sword, came in pastel shades, and when unsheathed it looked like a flower from outer space.

A lightweight, molded plastic chair designed in the late ’90s by Mario Bellini, the Italian architect and industrial designer, was another hit for Mr. Heller — and his first piece of furniture. It is an essentialist object, a chair reduced to its purest form, and economical, originally priced at under $100, in keeping with Mr. Heller’s ethos of attainable design.

When the retailer Design Within Reach opened in 1999, the Bellini chair was a featured product in its first catalog, and for years it was among the company’s best sellers. It earned Mr. Bellini a Compasso d’Oro in 2001.

(In 2009, Mr. Heller sued the company for knocking off the chair — the Bellini-manque was named the “Alonzo” and priced at about $50 less than the original — as did a number of designers who were also being copied. New management stopped the practice, and the original Bellini chair is “still a consistently selling classic,” said John Edelman, a former chief executive of Design Within Reach.)

“Alan wanted to do what was unusual,” said Gordon Segal, founder of Crate & Barrel, an early source for Heller dinnerware. “He never wanted to do what was easy. Hellerware was hard to produce, and it cost twice as much as other plastics because of its unique construction.”

He added: “Plastic in those days was ugly, and it was cheap. But Alan and the Vignellis had made something that was beautiful, and it could be abused. You could put it in the dishwasher. You could drop it. And it lasted forever. My family still has an original set. It was hard to merchandise at first. We had to convince people that plastic was worth paying for. It took courage for Alan to do what he did.”

Alan Jay Heller was born on May 13, 1940, in Port Chester, N.Y., and grew up in nearby White Plains. His father, Jacob Heller, manufactured aluminum housewares, notably Heller Hostessware Colorama, a line of anodized aluminum pieces that included a set of rainbow colored tumblers — a midcentury classic — and a rotating cake platter that played “Happy Birthday.” His mother, Ruth (Robinowitz) Heller, was a homemaker who died of breast cancer when Alan was 13. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the New School for Social Research in 1965.

An early marriage to Beverly Glassenberg ended in divorce. In addition to Ms. Bluestone, Mr. Heller is survived by his sisters, Suzanne Heller and Faith Willinger.

Besides the Vignellis, Mr. Starck and Mr. Bellini, Mr. Heller’s company, Heller Inc., made furniture for other designers, including Frank Gehry — Flinstonian indoor/outdoor sofas and tables in primary colors — and Studio 65, for which he produced a dramatic bright red sofa shaped like lips.

“Without guys like Alan,” Lester Gribetz, then vice president of Bloomingdales, told the design writer Arlene Hirst in 1985, “this would be the dullest industry in the world.”

Source: Read Full Article