5 Art Gallery Shows to See Right Now

05/24/2021Rowan Renee

Through May 30. Five Myles, 558 St Johns Place, Brooklyn; (718) 783-4438, fivemyles.org.

Of the 44 artists featured in the 2020 exhibition “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” at MoMA PS1, most produced work while serving prison sentences. Rowan Renee was an exception. Renee, who identifies as genderqueer and uses nonbinary pronouns, is the child of a prisoner. Their father was a convicted pedophile who died in jail, and Renee’s installation, “No Spirit for Me,” consisted almost entirely of related court and police legal documents that the artist had painstakingly recomposed as lithographs on handwoven fabric panels. Together the panels revealed the official history of one crime, but only hinted at the history of another, namely the abuse Renee had experienced as a child at their father’s hands.

A new installation at Five Myles, “That Day, We Looked Happy,” takes up that personal history. At the center of the piece are, again, woven documents, in this case family letters Renee inherited after their father’s death. But primary documentary material here is photographic: scrapbook snapshots of Renee’s father seen posing with wife and child. Some of the photographs have been altered by the artist, cut up or stained. Most have been embedded in frames of molten glass, making them look like relics of a cosmic meltdown. Where the earlier installation was unrelentingly sepulchral, this one has, in the snapshots and glass, spots of color and light. It continues this artist’s labor-intensive address of personal trauma with a new, complicated mix of compassion, bitterness and regret. HOLLAND COTTER

Darrel Ellis

Through May 28. Candice Madey, 1 Rivington Street, Manhattan; candicemadey.com.

Darrel Ellis grew up in the Bronx without his father, an amateur photographer who was killed by the police not long before Darrel was born. But when Darrel was 20, his mother gave him an archive of his father’s family photos. He spent the next 13 years, until his death of AIDS at the age of 33 in 1992, examining them, as if searching for the key to a lost connection. He copied them with ink and brush, and he rephotographed them, sometimes altering them first by projecting the negatives onto little ziggurats of plaster.

“A Composite Being,” a show of Ellis’s paintings, photographs and works on paper at Candice Madey, includes several gorgeous self-portraits made toward the end of his life. Their precision is astonishing: In one, the artist’s expression is concentrated but slightly suspicious, as if his own attention unnerved him. In another, he’s distant but vulnerable, a person who keeps getting hurt but can’t stop showing up. Still, it’s clear that what most interested Ellis about ink was the tones it offered, from glittering black to smokey gray. It made a good stand-in, in that way, for love, or for grief — emotions too dense to see through when they’re happening, but which inevitably fade and dissipate. WILL HEINRICH

Lu Yang

Through June 19. Jane Lombard Gallery, 58 White Street, Manhattan; 212-967-8040, janelombardgallery.com.

Lu Yang’s work has not appeared frequently in New York, which is surprising since she is rather well known internationally. (She was included in “Micro Era: Media Art from China” in Berlin from 2019 to ’20, for instance, which showcased significant artists from China.) Her new exhibition, “Doku: Digital Alaya,” at Jane Lombard, also feels more like a coda than an introduction. Where earlier videos like “Uterus Man” (2013) and “Lu Yang Delusional Mandala” (2015) sent viewers on hallucinatory journeys exploring the human body through both digital reality and traditional Buddhist ideas, this one is simpler.

Doku is a nonbinary avatar who appears in a series of stylish lightboxes and videos, outfitted in a jazzy bodysuit with a design that resembles computer circuit boards or veins and arteries. Six different environments surround Doku, each representing a realm of rebirth in Buddhist reincarnation, but updated. The “animal” realm, for example, is an industrial meat-processing plant. The show also includes behind-the-scenes video showing how Lu Yang creates her work, with the aid of animators, scientists and performers.

None of this is as mind-bending, as say, “Lu Yang Delusional Mandala,” in which the artist — or her scanned digital image — underwent radical physiological transformations, including death. “Doku: Digital Alaya” might be a resting point though, before Lu Yang sets off on another posthuman odyssey, exploring human bodies and worlds altered by digital technology and commerce. MARTHA SCHWENDENER

Kunle Martins

Through May 28. Bortolami, 55 Walker Street, Manhattan; 212-727-2050, bortolamigallery.com.

In the early 2000s, the influential and anarchy-flirting IRAK graffiti crew courted stylistic innovation and nihilism in equal measure (the name comes from “racking,” or shoplifting), becoming a lodestar in New York City street culture and a locus point of a wilder version of the city that has by now been mostly smoothed over. Its members and associates have either moved on to respectable art careers (Ryan McGinley, Dan Colen), or self-destructed (Dash Snow, who died at age 27).

For the last few years, Kunle Martins, who founded and led the cohort, has moved away from tagging, making delicate graphite and charcoal portraits of friends, often on found cardboard, creating an intimate assembly of a downtown demimonde. For his new show, “S3ND NUD3S,” Martins requested nude selfies from his friends, the most modern mediation of self-portraiture, which he translated into tender evocations, attentive but unidealized, like an especially faithful frottage, or a Tom of Finland given a cold shower. Here they’re life-size or blown out, their rubbed likenesses vibrating between starkness and a half-remembered dream.

The humbleness of the cardboard, sometimes collaged into a larger plane, recalls the assemblages of Ray Johnson, who favored dry cleaning inserts, and Kurt Schwitters, whose radical creative freedom found beauty in trash. That material also returns them, spiritually, to graffiti — making what’s ignored visible, and connecting his subjects — Colen, Jack Pierson, a pregnant Chloë Sevigny — both to the grit of street life and the fleeting nature of the city itself. MAX LAKIN

Keltie Ferris

Through May 29. Mitchell-Innes & Nash, 534 West 26th Street, Manhattan; 212-744-7400, miandn.com.

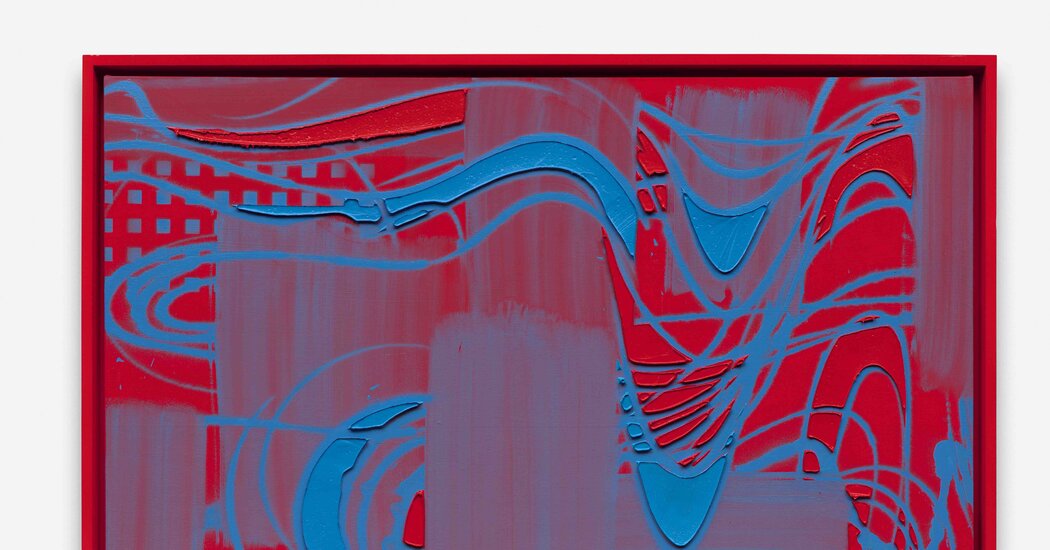

Each of the 12 large-scale paintings in Keltie Ferris’s exhibition “FEEEEELING” is set within a handmade frame, and all of them were made in the past year. Considered together, the paintings act as an inventory of the innovative techniques the artist has used over the past decade. A series of looping monochrome compositions made with graphite give way to compact geometric assemblages, which are interspersed with multilayered paintings made by imprinting canvas onto canvas. This is Ferris’s trip down memory lane, but the works still feel fresh. Drawn directly onto the Sheetrock that spans the gallery’s back wall is a new site-specific drawing, “Xstatic Being Xstatic” (2021). Read this as an index to Ferris’s entire practice. Made with graphite, its dense conglomerations of curves and straight lines are replete with smudges, clues that prove that learning the artist’s process is integral to appreciating the final product.

Ferris’s paean to the transportive possibilities offered by drawing — what Paul Klee called “taking a line for a walk” — showcases how a sense of movement can be conveyed through artistic restraint. Rejecting a hard disciplinary line between drawing and painting, Ferris revels in that more exhilarating space that emerges between mediums, which allows instinct and intuition to take the lead. “S=t=r=e=a=m=s” (2020-21) highlights the thrill of this intermediate zone, its lurid combination of electric blue and bright red paint layered with sculptural thickness and an array of brush strokes that alternate hard-edge geometric forms against a gridded background. Variations of these gestural abstractions crop up across the exhibition, each painting bearing a loose but decisive inheritance to post-1980s German and American abstraction, which still excites because it did away with abstraction’s stodgiest rules. Ferris’s ingeniousness, however, is more of a self-critical expansion of his own techniques than a gaze back at the canon, making his style resolutely one of a kind. TAUSIF NOOR

Source: Read Full Article